Excavating Tai O, a village trapped between past and present

When I tell my mother I'm going to Tai O fishing village for the day, she tells me a few things:

1. Join a Chinese pink dolphin sightseeing tour.

2. Go to Tai O Heritage Hotel.

3. Bring her back salted eggs and shrimp paste.

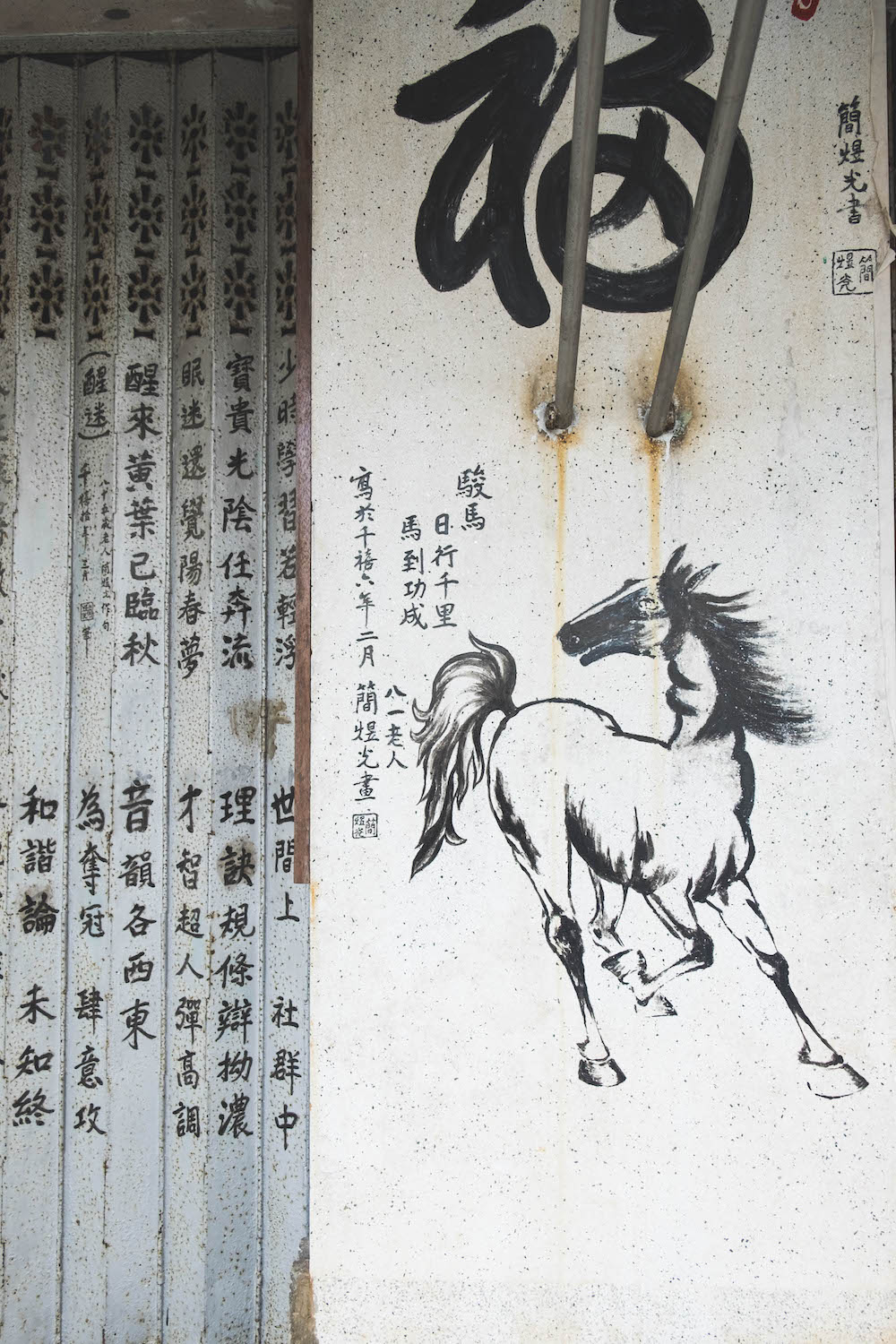

As Hong Kong locals, these are the kinds of things that we would tell any of our visitors and is just about as touristy as it gets. Even for those of us that have lived in the city for over twenty years, there's a certain magical quality to Tai O as a place seemingly frozen in time with its Tanka stilt houses and fisheries - the same rose-tinted view of Havana with its vintage cars and old architecture.

Located at the mouth of the Pearl River, Tai O was once a powerhouse with a booming fishing and salt economy. It was so wealthy that during the British occupation a police station was set up to tackle the pirates who would target its residents.

However in recent years, their industries have declined, younger generations have moved inland to chase their fortune and the things that once were hallmarks of the village's affluence have been transformed into tourist attractions for those driven enough to make the trek out to the western coast of Lantau Island.

The ride out to Tai O is a long one, starting in the skyscraping financial district Central on the MTR before flagging down a distinctive blue taxi or bus to take you through sprawling emerald mountain terrain. The closer we get to Tai O, the less like the postcard cityscape Hong Kong it feels as the crowds disperse and there's not a building taller than three stories in sight.

Iris Wong, one of the project committee members behind the Hong Kong Heritage Conservation Foundation, as well as her assistant Marian Yeung meets us at Tung Chung station and thankfully drives us to the village. She talks a mile a minute and about nothing else but the village.

Over the course of our conversation, I'm surprised to hear that she's actually never lived there and lives further inland on the main island. However as part of the team that helped convert Tai O's abandoned colonial police station into Tai O Heritage Hotel, she's become incredibly attached.

Case in point, she comments on the torrential rain beating down on the car and explains how Tai O Village goes into shutdown mode when the typhoon rolls in. Residents move further inland and out of the stilt houses in case they don't hold. However during the last big typhoon, Iris had actually been staying in the boutique hotel for a getaway weekend.

“Everyone was telling me to go home. [Tai O] is my home.”

It's not hard to see why the village inspires such loyalty. As the rain clears and we finally reach the village, the emerald mangroves wave hello alongside the pier and we follow a path round to Tai O Creek, where stilt houses teeter precariously over the low waters and bright boats bob along.

Iris greets and then sidesteps the older men and women hawking guided boat tours and instead makes a beeline for a motorised sampan, a Chinese fishing boat, that will take us directly to Tai O Heritage Hotel for a quick meal.

Tai O's earliest residents, the nomadic Chinese Tanka tribe, founded Tai O village out of necessity during the Ming Dynasty. Looked down upon by the rest of the Hong Kong population, they were banned from living inland and found a loophole by building homes on stilts by Tai O Island where they could dock their boats. They lived their lives on the water and boats were a crucial part of their lives, as many made their living by fishing and creating salt, though those industries have since been diminished.

Fishermen and women who once cast their nets out to make a living now have shinier, neon orange boats provided by the Hong Kong Tourism Board to ferry around passengers for HKD$40, though occasionally I catch a sampan skimming past. With many of Tai O's residents descended from the Tanka tribe, it's moving to see how newer generations may have changed with the times but have found ways to retain their close connection to the water.

Tai O Heritage Hotel

Our sampan docks at Tai O Pier and the ivory Tai O Heritage Hotel oversees us coolly, nestled on the side of a mountain facing outwards to the sea. While the hundred year old structure may have gone through a number of face lifts since it was first built, it remains steeped in history.

Built by the British in 1902 during their occupation of Hong Kong, it was one of the first colonial police stations to be formed in the New Territories. Tai O Village was once subject to pirate raids, targeted because of the wealth its once booming fishing and salt-making industries once brought them and proximity to the water, and its main purpose was to serve as a deterrent to future raids.

As we enter the building, small dents in what was once the Report Room door are pointed out to me - scars from a murder-suicide in which Indian police officer Teja Singh shot his commanding officer Sergeant Thomas Cecil Glendinning following a theft accusation, which ignited a conversation about racial tensions all over the city.

Despite its years of service to the Tai O villagers, it performed its job perhaps too well and was downsized to a modest patrol post in 1996 before being totally abandoned in 2002. For ten years, it sat in a state of disrepair until Iris and her team came along with a grant to give it a new lease on life it in an ambitious twenty two month restoration project. As with the rest of Tai O, it has somehow endured the relentless tide of modernisation by preserving its roots, yet pivoting towards curious travellers.

The building is stunning, with tall balconies perfect for spotting the occasional pirate and a number of modest rooms with quirky names such as Sea Tiger (formerly a sub-divisional inspector's office) or General's Rock (the old briefing room).

The true gem however is Tai O Lookout, a restaurant located on the hotel's upper floor, with ceilings and walls made entirely out of glass that oversee the dramatic horizon. Everything from the art over the hotel beds to the menu is carefully considered and imbued with local traditions and history.

As we relax at a table, Marian shovels fried rice made with Tai O's signature shrimp paste onto my plate and Iris orders a round of drinks that look like a bottled sunset, made from a root native to the village named Mountain Begonia.

Along the tour, we're taken to reception where a tiny jail cell filled with souvenirs sits, as well as a series of police-themed props for a photo opportunity. I feel incredibly awkward as I pop a hat on and climb in, posing as a black and white video details the duties of the policemen who once worked here but as new guests to the hotel pour in to check in and form a line after me, I think of how this building would have been nothing but a ruin without a dash of tourism.

Baby Orchid

Iris and Marian have spent the whole day talking about Baby Orchid, a woman who seems to be a regular Tai O celebrity, and it becomes apparent that I need to put a face to the name. When I first meet Baby Orchid (whose real name is Hung Wai-Lan), the eighty year old photographer and opera singer is tucked away at the back of a café in one of the stilt houses.

She is sitting at a table with a huge group of people who must be at least forty years younger than her, however her stylish glasses, bright floral shirt and hoarse, charismatic laugh make her the most vibrant person there. Marian points her out, referring to her by her nickname Baby Orchid, and rushes over to make our apologies for being so late.

She waves her off dismissively and says her goodbyes to the group before settling at a table overlooking the creek. Motorised sampans rumble by in the low waters. In rapid Cantonese, she tells Marian something and she bursts out laughing. Then she turns to me and translates: Baby Orchid had no idea who those people on the next table were. She just sat down and struck up a conversation with them, forcing her way into their little group.

Even before meeting her, I've been told she's essentially the queen socialite of Tai O Village despite the fact that she doesn't live there anymore. As we conduct our interview, she reminds us she has a dinner appointment in the village she has to get to shortly afterwards.

Just a few minutes later, her ringtone (a shocking wail of Cantonese opera) signals another friend trying to catch her before she goes back to the main island. The strangers she had just met stop to wave goodbye to her as they leave and it seems the woman has a knack for drawing people to her, as well as drawing out their stories.

She was born and raised in Tai O Village, however unlike many of the residents in the town, her family steered away from water-related careers. Instead, they set up shop as the only photographers in the village - a skill that they passed onto her.

For years, Baby Orchid and her family captured and developed the faces of Tai O's residents in their own darkroom, becoming the village's photography "one stop shop". Wielding a Rolleiflex, a keen eye for candids and a natural curiosity about people, it's no surprise that her skill lay mainly in portraiture but not the kind you'd normally expect.

"All these fishing villagers had to go out to fish...so in order to do so, they had to apply for a license. And for the license, they had to have an ID photograph," Iris helpfully mediates, as Baby Orchid nods.

Licensing was something that was handled at the time by Tai O Police Station and it becomes impossible not to talk about the British structure, a colonial sore thumb amidst a sea of stilt houses. It turns out that Baby Orchid used to take a lot of photographs of Tai O Station and scoffs a little when asked about it. Back in her day, the policemen would hang around after their shift at the lookout point and keep their eyes peeled on Tai O Pier for the sampan that would arrive.

“They [would] all collect there...to look at all these beauties like a catwalk, getting off boats.”

Was she one of those beauties? Naturally. They courted her incessantly, she tells me. I ask her if it there was anybody in particular that had her eye on her. She waves her hand regally and rattles something off in Cantonese. The table bursts out laughing before I can understand the joke - apparently, everyone's still after her.

The town's population has gone through a massive change, shifting from 30,000 residents to roughly 2,000 in 2002, as industrialised fishing and other modern advancements diminished Tai O's former powerhouse industries and people moved inland for work. Baby Orchid was amongst them, however she moved for love rather than her career.

"None of [the policemen] were successful," she says of their attempts to court her.

Instead, she fell in love with a surveyor from the city when he visited Tai O on a routine visit. Before long, they were married and she left the stilt houses for high rises, but can frequently be found nowadays having tea in Tai O. She tells me she returns to her hometown whenever she thinks of it and wants to chitchat, both of which happen more often than not.

While many of the people that Baby Orchid once knew have passed on or moved away, she still knows the families that reside here and have their photographs. She's captured weddings, births, family portraits and stunning candids that have since been featured in books about Tai O.

From her bag, she proudly produced a folder full of press cuttings and points at an interview she conducted for SCMP's Post Magazine, an offshoot of Hong Kong's leading English-language newspaper. Posing with her Rolleiflex and dressed in yet another bright floral, the headline MADAME PHOTO arc across the top of the page.

More recently, a photography exhibition was held for her to showcase her long buried images and the venue bustled with local residents, clamouring for a chance to spot their relatives as they had never seen them before. Her photography has made up the fabric of Tai O's history, just as it has been intertwined with that of its residents.

Baby Orchid and her photography are portals to Tai O's chequered past, however as with the fishing village, she isn't frozen in time. As we prepare to go, she pulls out the digital Nikon point and shoot camera in her purse to snap a photo of me before I head off; Rolleiflex nowhere to be found.